Arianny Torres packed a few changes of clothes, a couple of toys, medicine, diapers, a baby bottle, photos of relatives and her bible into a small suitcase. With her two young children, Lucas and Aleska, she traveled 606 miles (976 kilometers) from Maracaibo to Bogotá. Sometimes they were lucky and hitched a ride. Other times they caught a bus, cutting into the small amount of money Arianny had put aside for food. Arianny is determined to provide a more hopeful life for her kids. She sells candy in Bolivar Square and though she knows things could be better, at least life is more stable than it was in Venezuela and her kids are able to eat three times a day, which, says Arianny, is a blessing.

Since 2014, faced with an increasingly dim economic and political situation, Venezuelans have been leaving their country in droves. In fact, the UNHCR estimates that there's been an 8000% increase in Venezuelans seeking refugee status in the past 5 years, which has led to 4 million people now living abroad. It's in this context that photographer Gregg Segal raised his lens to capture some of the faces that have been affected by these changes.

Undaily Bread is the follow up to Segal's successful Daily Bread series, which saw him photographing children around the world surrounded by items from their daily diet. This time, in collaboration with the UNHCR, Segal is telling the story of the women and children who have been forced to flee their homes, many traveling over 600 miles to safety. All of them now live as refugees in Bogotá, Colombia and are attempting to construct a life that is better than what they left behind.

Items from their daily meals are strewn about them, accompanied by the few precious possessions they were able to bring from home. Viewing these items is a stark reminder of the conditions these families are facing, have fled economic hardship and now working to create a new future for themselves. With job opportunities scarce, many of these families are struggling to make ends meet. To this end, the UNHCR used Segal's photographic series as a way to raise funds to cover medical care for Venezuelan refugees.

We had a chance to speak with Segal about how the collaboration came about and what he hopes people take away from the stories of these families. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Yosiahanny left Venezuela with her two daughters—one was not photographed—and a baby on the way. She’d prepared a dozen arepas for the road and collected enough money to buy formula for her little ones. She packed a few changes of clothes, her bible, and the teddy bear grandma had given them in farewell. Yosiahanny’s husband had been waiting for them in Bogotá, where he’s been working as a security guard. Despite his job, money is very tight. Their landlady is losing patience with the refugees who rent rooms in her home. Yosiahanny and her family will have to move again soon. Though life in Bogotá is a struggle, Yosiahanny is able to get the medicine and supplies she needs and is able to eat more than once a day. What makes the crisis tolerable is love, she says.

How did the concept for Undaily Bread come about?

I was contacted by Jose Racioppi, a copywriter at Publicis in Bogotá. Jose had seen Daily Bread and approached me about doing a series in the same vein, but one focused on the Venezuelan immigrants who’ve sought refuge in Columbia.

How did the partnership with UNHCR develop and how did they help you move forward with the project?

Jose set up the partnership with UNHCR and together we worked through the details and discussed how we would use the pictures to raise funds for a UNHCR campaign. Donors would receive photographic prints as rewards for their contribution and money raised would help cover the cost of essential medical care for mothers and children who’d fled to Bogotá.

Nathalia Rodríguez, 9 years old, photographed September 27, 2019 in Bogotá, Columbia. Nathalia walked from Barquisimeto, Venezuela to Bogotá with her mother. They took a few necessities (clothes, blankets, a book of Biblical stories). During the seven day journey, Nathalia ate only bread, cookies, arepas, packaged chips, water, juice, two lollipops, and the one fruit they could afford, bananas. It’s been three years since Nathalia ate an apple because a single apple costs more than 5,000 Bolivas, about $500 US. Nathalia is a resilient kid, but without basic necessities like nutrition and health care, her future is in doubt. This portrait was shot in collaboration with ACNUR, the United Nations refugee agency, to help raise awareness about the plight of refugees and to raise funds necessary to provide mothers and their children with check-ups and other basic medical care.

How did working on this series challenge your preconceived notions of what these families go through?

I think the process supported what I knew about the plight of the refugees. I suspected that they'd had very little to eat during their journeys from Venezuela and this was the case. I’d heard about the collapse of the Venezuelan economy. With inflation spiraling out of control, money in Venezuela is virtually worthless. One of the kids I photographed, Nathalia, hadn’t eaten an apple in more than three years because of skyrocketing prices. A single apple cost more than 5,000 Bolivias—about $12. We had apples in the studio during the shoot and it was so great to see Nathalia munching on one!

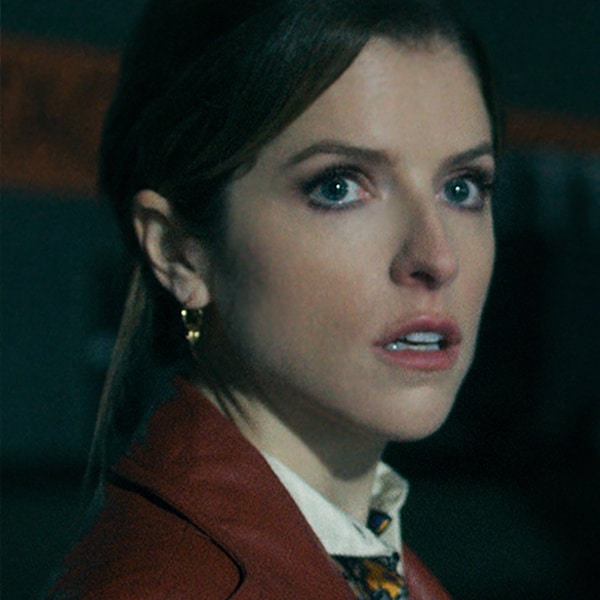

Michell, 19 years old and a single mother, made the trip from Venezuela with her two young children not once, but twice. The first time she arrived, she was sent back to her country. Determined to find a better life for her kids, Michell made a second attempt. While on the road, she had an epileptic attack and lost consciousness. It took Michell and her kids 16 days to reach Bogota this time. Michell’s life in Bogota is far from secure. She makes a meager income selling newspapers at the TransMilenio, though not enough to cover the cost of her medication. In this photo, Michell’s son is pretending to be a bus driver. His carefree energy sharply contrasts his mom’s concern and worry, as she glances at her squalling, inconsolable baby. Michell’s meager possessions and food tell the story of how hard life is for her family. After our photoshoot, Michell’s son carried two loaves of bread around the studio, not wanting to give them up, not wanting to feel hunger again.

How did this experience contrast or compare to working on Daily Bread?

With this project, I looked not only at what kids and mothers ate during their journeys but also at what they carried with them from home. It was important to underscore how little refugees are able to keep from their lives in Venezuela. It’s as if your house were on fire and you only had time to grab a few cherished keepsakes and the barest of necessities. One mother took her son’s last homework assignment from school, a simple but meaningful detail of his childhood that would otherwise be lost.

Why do you think it's important for artists to become involved with social issues?

Artists can illuminate social issues by framing them in a way that hadn’t been considered or by visualizing problems in ways that hadn’t been clearly seen or felt. I think artists can help us feel and can ignite compassion with their work. Images connect with audiences on a gut level. We live in a visual age and pictures convey social problems with immediacy. The old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words has never been truer.

Yudith and her son Williams, 7 years old, fled Venezuela and walked more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) to reach Colombia. Yudith fled alone with her youngest child, leaving behind her adult sons because she felt it was the only way to give Williams a chance in life. When I met Williams, he showed me his tattered backpack. In it, he carried a few things from home including the last homework assignment from his old school, something he was proud of. On the long walk from Venezuela, Williams and his mom ate only bread, a few pieces of fruit, and drank only water.

Is there any family in particular that stuck with you?

They all stuck with me—from the little boy who carried bread around after the shoot, tucked securely under his arm, because he didn’t want to feel hunger again to the mother who fled alone with her youngest son, leaving behind her adult sons, because she knew it was the only way to give him a chance in life. She’d been determined to get out and on to a more hopeful life before it was too late, before this child’s optimism was ground down.

What do you hope that people take away from the series?

When we look at photographs we often see ourselves in others. It is one of the most vital capacities a human being can have—empathy. I would hope that the simple, direct presentation of refugees opens this well of empathy in viewers and they ask, what if it were me?